Contents

ToggleSaving the voice of the fields

The Alentejo is a land of slow living, where the beautiful landscape unfolds like a painting. The soundtrack to the ancient olive groves and frozen centennial cork trees is the gentle ding, ding, ding of cowbells. It’s not uncommon to cross paths with a shepherd, letting his flock roam free in the pastures. But not too free; they still need to find the animals and be able to tell their sheep or goats from their neighbours’. Thank goodness for bells!

A tradition passed from father to son

The making of cowbells is a craft traditionally passed from father to son, and it has a long history in the village of Alcáçovas, south of Évora. Here you can visit Chocalhos Pardalinho to explore the art of making cowbells. I was not expecting much – cowbells are just a sheet of metal, right? – but was absolutely mesmerised by the technical and complex process of making and tuning (yes, tuning) these artisanal bells.

At the end of July each year the town of Alcaçovas holds the Feira do Choalho, a fair celebrating the town’s tradition of cowbell making. In 2025 the festivals fall from 25 – 27 July. More information.

Witness the art of making chocalhos

There are only a handful of men left dedicated to the craft, so it felt very special to see the whole process. It starts, as you’d expert, with a sheet of metal, which varies in thickness depending on the size of the cowbell. The master artisan slices it to size then bends it around an anvil with a hammer. Here he bangs in ears, and adds a handle and the céu (heaven), a little loop where the badalo (clapper) will hang.

Read next… 18 best places to visit in the Alentejo: prettiest villages, towns and cities

Into the oven they go

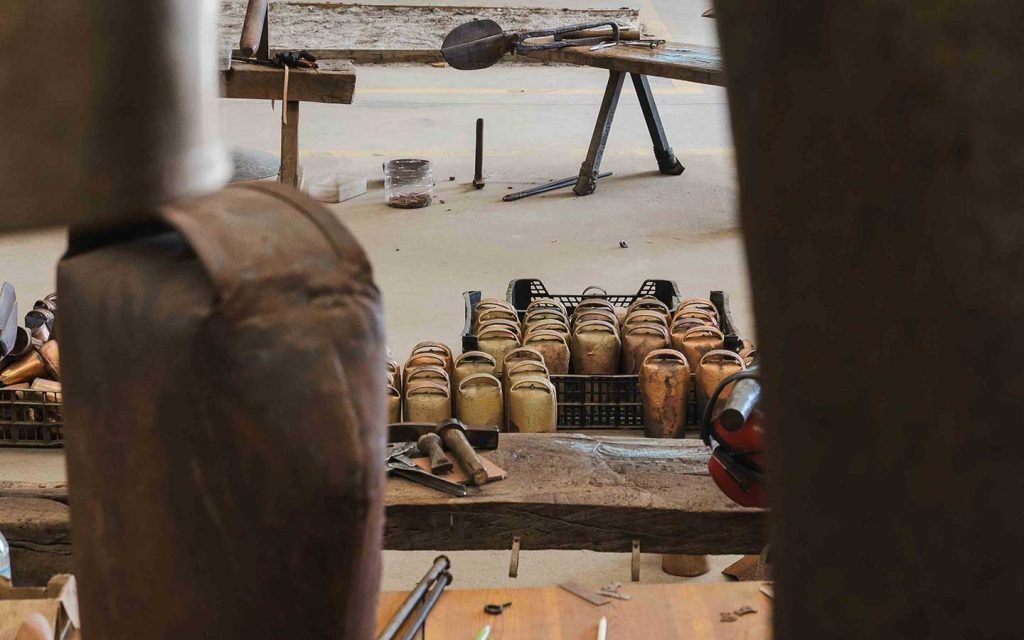

The bell is wrapped in paper, then a few pieces of brass are added before it gets cocooned inside a shell of clay and straw with a hole poked into the cavity. That’s left to dry in the sun.

Once dry, the bells are baked in an oven for about an hour at 1,250°C. While still piping hot, the craftsman removes them with a hook, rolling each on the floor so that the melted brass covers the bells evenly. The chocalhos are submerged in water to cool down, then the shell is cracked off to reveal a glistening golden bell – much prettier than the iron one that went in.

Each bell is then individually tuned

The brass helps make the cattle bells last longer, plus it gives each bell a beautiful sound. Each bell is tuned by a master with decades of experience. The goal is to make each bell create a strong, long and pleasant sound that will travel across the plains. The bells are adjusted to remove any unstable sound waves.

Apparently some shepherds will request a specific note to signify their flock – that might mean making 100 bells for an order of 20 to get the tones right. Once tuned, the bell is polished and the wooden clapper and a leather band are added.

Read next… Portugal’s pottery village: Why you should visit São Pedro do Corval

On UNESCO’s list of Intangible Heritage

The art of making cowbells has been slowly slipping away due to a few reasons – beyond more industrial techniques, there are less shepherds and more farmers with fences (who have no need for bells to identify their flocks).

Portugal’s chocalhos have been classified as UNESCO Intangible Heritage of Humanity to try and preserve this ancient craft. There are just 13 master craftsmen left, and only a handful of those are under 70 and still working.

Where to experience the art of cowbell making

If you’re interested, you can email or call Chocalhos Pardalinho to see this all for yourself at their workshop in Alcáçovas. It sounds like they have a “bell maker for a day” experience too. When I was there the younger apprentice showed us how it was done and he spoke really fantastic English.

Also in the village you can visit the Museu do Chocalho (Cowbell Museum) to see a private collection of more than 3,000 items gathered over 60 years.

If you can’t make it to Alcáçovas, there is another family of chocalhos – the Sim Sim family – in Estremoz who have run the Casa Galileu shop for more than 50 years. Inside you’ll find bells made by three generations of the same family along with other crafts from the region.

I visited Chocalhos Pardalinho with the help of Visit Alentejo.

Read next…

- 48 hours in Évora

- Where to shop for Portuguese ceramics

- My 10 favourite Portugal trips in 2024

- Where to shop Portuguese ceramics by weight & pottery outlets

- 18 best places to visit in the Alentejo: prettiest villages, towns and cities

- Portugal’s pottery village: Why you should visit São Pedro do Corval

- Where to shop in Évora: artisans & boutiques

- Bottomless wine and secret cellars: Redondo’s tasca and talha trail

- Hotel Review: A dreamy weekend at Hotel Convento de São Paulo